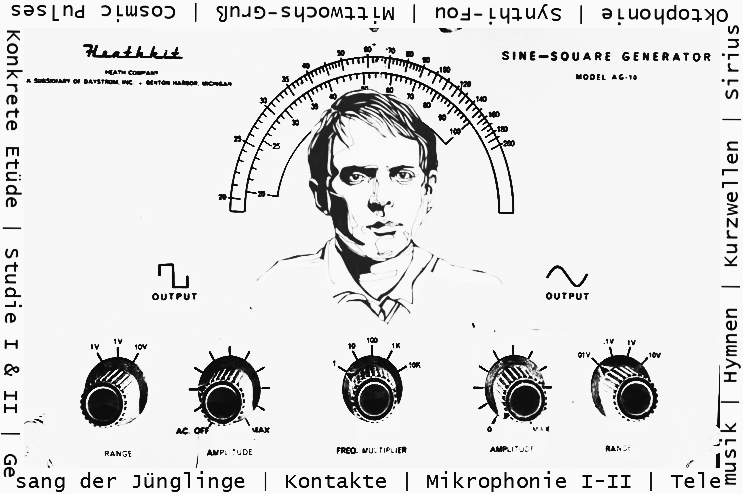

KS and an old friend (Heathkit signal generator)

Aries from SIRIUS (1977)

Klavierstück 13: Luzifers Traum (1981)

Refrain (1959)

Kreuzspiel (1951)

INORI (1974)

I was deeply into postwar modernism at age 20: Boulez, Ligeti, Carter, Berio, Babbitt, Feldman, and the later Finnissy. Density of sonic information was therapeutic during my most depressed years. It pushed past the fog of depersonalization and derealization. Not to say I was familiar with much – I was limited to an occasional CD and the offerings on Limewire. Among the daunting stuff available were Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Klavierstücke 1 through 11. I missed the sheen and brutality of the Boulez sonatas. Delving further into his work only becomes more confusing due to the stylistic and technical drift. Open form; shortwave radio pieces; ‘intuitive’ music; signs of the zodiac playable on any instrument…and that’s all before operas with helicopters and camels. This is the master of European total serialism?

Admirers ambivalent about aleatorics still consider Mantra (1970) – a return to fully prescribed composition – to be as brilliant as Stockhausen 1950s classics.1 Yet numerous former advocates did not come back. The forbidding enormity of LICHT and the composer’s mutual disengagement from Nono, Maderna, Cage, Boulez, Berio, et al. help explain why fans of Gruppen remain unaware of the late KLANG cycle (2004-07).2 It is not irrelevant that KS turned out to be the serious (but slightly goofy) mystic among a circle of aesthetes and leftists: truly a disciple of Olivier Messiaen, even if certain critics would rather compare him to Billy Meier.

This is a meandering preface to highlighting FIVE of Karlheinz Stockhausen’s works . . . not the storied ones in chronicles of electronic music and postwar serialism, but favorites that I can step into or away from; that I can listen to closely or passively– not something I’d say about the youth song, groups, contacts, hymns. Those deserve their laurel wreaths; this is an alternate grouping of less conspicuous classics that are, dare I say, accessible? Like Prince’s B-Sides; or perhaps A Plaine and Easie Introduction to Avantgarde Musicke.

ARIES from SIRIUS (1977) for trumpet and recorded tape

The Tierkreis pieces (1975) are unusual Stockhausian classics – maybe his most popular in frequency of performance. The zodiac works find new lives through polyphonic and monophonic realization. What I like best is their equal openness to performer and composer reinterpretation, as Stocky himself found several new contexts for the tunes. Aries is one such tune that found considerable development as one of the featured melodies in SIRIUS. As with LICHT, component parts of SIRIUS can be extracted for solo performance. Aries works excellently as a self-contained solo of rich timbres and rewarding, if not unflashy challenges of tape coordination, breath control, and mute changing. Trumpeter Elisabeth Lusche discusses it here.

I’d advise the curious to listen to the “Aries” music box (See above); then to hear it as part of the strangely, choreographed Musik im Bauch (1975). Next, check out how several people play the work on guitar, trumpet, other possibilities…before turning not to the derivation from SIRIUS. This is one of those ‘you’re going to have to trust me’ pieces in that there is no easy-to-find recording of the entire work. Markus Stockhausen’s on the comp. Music from Outer Space is missing the final 3-4 out of fifteen minutes: it only reaches the trumpet introduction of “Taurus” and abruptly stops. This is cutting off a three-movement trumpet sonata before the finale. In a beautifully balanced work, it frustrates.4

But I assure you! This is a wonderful trumpet + synthesized tape piece and should be performed more often. Some fans lament the loss of Stockhausen’s early synth tones: the EMS Synthi 100 here is far cry from the handmade additive synthesis of the 1950s and 60s. I think that much like Pauline Oliveros‘s transition from live-dialed signal generators to modular synthesizers, Stockhausen was also able to adapt new tech to his musical impulses in these unusually relaxed, almost ambient textures. As in other Karlheinz-Markus Stockhausen collaborations, the varied mutes and articulations produce fine speechlike gradations of sound.

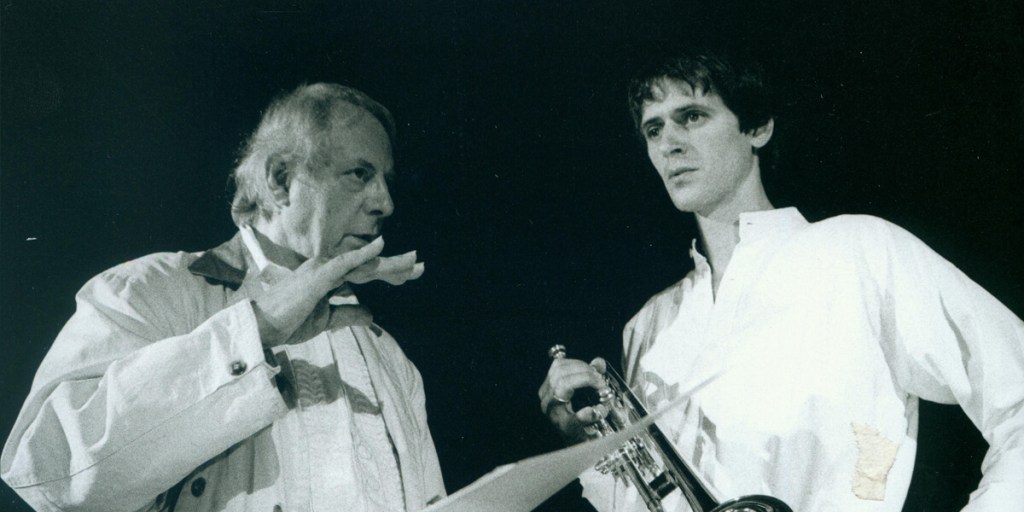

KS and son Markus Stockhausen. Credit to the Markus Stockhausen website.

KLAVIERSTÜCK No. 13: LUZIFERS TRAUM (1981)

With exceptions, the classic Klavierstücke 1-11 do not yield an immediately grasped ‘character.’ The special regard many hold for the beautiful No. 9 is directly related to its specificity of affect: steadily pulsing chords interspersed with freer fantasien.4 Like No. 12, No. 13 emerges from LICHT and bears traces of Stockhausen’s 1970s developments. Where 12 – extracted from Donnerstag aus Licht – is whimsical, 13 has a heavy air and serious intent evident with or without its operatic context in Samstag.5

Luzifers Traum scene from Samstag aus Licht by Le Balcon (Paris, 2019). Photo Claire Gaby,6

Stockhausen’s cantus firmus-like augmentation of melodic figures (formulae) into larger units has lush consequences. Free from the constant serial churning, he concentrates on ways to enrich a sparsely detailed canvas – as his primary ‘structural’ pitches proceed at leisure. Vocalizations (whistling; whispering; the telltale counting that is Lucifer’s trademark), treating the piano body as percussion, and scraping the piano strings are added to Stockhausen’s characteristic glissandi, Nachklänge, and assorted pedaling. Lucifer dreams LICHT’S melodic structures in slow motion as the oneiric mind generates experiences in diminution that feel in real time.

1950s Stockhausen had an truly theatrical panache for dramatizing serial pitch and rhythm through so-called secondary parameters such as timbre, registration, space – effectively raising them to primary status, and always finding room for climactic flourishes. Here the contacts are not so dramatic. Even INORI’s unfolding has a definite progression and goal, but this is a true mood piece, if not as ambient as Aries. Throughout several melodic rotations, he uses similar colors, tempo, and ornaments: he clearly wants the audience to sense large-scale repetition, even if the details are fuzzy. It’s timeless repetition without direction; a sleep paralysis dream cycle one can’t awaken from.

Tomoko Tazawa (1991) made the best live performance I’ve found (you must ignore the VHS hiss, however): she is situated between Helga Karen‘s more spirited approach (2022) and Bernhard Wambach’s classic dreaminess. Her fine articulations, variations in tempo, and theatricality are outstanding.

REFRAIN (1959) for piano, vibraphone, celesta, & percussion

KS worked well with classic ensembles but especially delivered when writing for unconventional forces – as in everything for percussion. Refrain’s three primary timbres are initially shrouded in shimmering group sonorities a bit like Studie II’s five-part-stacked sine tone timbres. Spoken syllabic outbursts confirm the formant / synthesized implications. Stockhausen really only specifies simultaneity and sequence of events: it is up to instrumental and room acoustics to yield real durations along with the intensity of attack. The crystalline bells throughout – antique cymbals join among other auxiliaries.

Relative durations according to decay meet relative polyphony in Zeitmasse–style group cadenzas where the musicians execute strings of notes as quickly as possible. These flurries open up the individual timbres. Meanwhile, the titular refrains mediate between the flurries and the ringing bells by splicing rich clusters, glissandi, and trills into the score. Stockhausen turns the ritornello principle into physical matter, as we the players position a glyph-dotted transparency on to the printed staves and feel the impositions as if splicing together tape segments.

Refrain is a clear favorite among fans and writers. If its possibilities for alternate interpretation are not as manifest as they initially appear (Ed Chang), the hybrid idiophone colors (and one chordophone) are so gorgeous that it’s impossible to complain. It’s exciting to read the beautiful score as you absorb their decays and anticipate the glittering refrains and cadenzas.

KREUZSPIEL (1951) for oboe, bass clarinet, piano, & percussion

Kreuzspiel is a youthful and appealing dramatization of Stocky’s timbral and pitch-space scenarios. The rhythmic repertory recalls early serialized duration schemes as in Messiaen’s chromatic rhythms; this meets a polyphonic equilibrium where all voices receive equal treatment – resembling the fragmentary 2-3 note imitation in Webern’s Symphony and Concerto. The waves of registral expansion and collapse are the defining Goeyvaertsian trace here; KS indicates the presence of

six notes in the highest octave and six notes in the lowest octave, and they are all played by the piano. And then one by one, each note crosses through the octave. At the end of the first movement, the six notes which were in the highest octave are in the lowest and vise versa.6

…but the Hauptsache is the theatre: how compositional detail enacts subtler serial dramas. He stages the registral premises by transmuting middle register piano to winds:

And the development / process can be clearly perceived because when they reach now into the three middle octaves, these notes are played by […] bass clarinet and oboe... And as each note is leaving the extreme position – one after another – one by one all the octaves, all the space will be filled until there is a middle section where all the octaves are filled equally… And then towards the end of the first movement, the middle region is again emptied and the notes are at the edges.

Feeling the bass clarinet and oboe take form – supplanting piano with far richer colors– and melt back to nothing is strangely moving. Without their presence, the registration games are lifeless.8 He also works wonders with his likewise expanding percussion palette. Is it not shocking for a serialist to open with a steady beat? The opening tumbas last just long enough for it to be internalized. I wish more composers of serialized rhythm would do us the courtesy!

INORI (1974)

It is surprising how often Stockhausen pieces resemble minimal music. It’s the affinity between concrète and noise; it’s the epiphany that all sonic phenomena are waves or pulses that Stockhausen uses to unite musical parameters. Whether you look at minimal means – process music and works with reduced notational conceits– or minimal yields, Stockhausen’s work has something to say. But as with Morton Feldman and Giacinto Scelsi, his stuff does not fit into ‘minimalism’– a relatively narrow quantity that was tightly contested and negotiated by the American musical establishment, as shown by Christophe Levaux.7

2012 staging of INORI by Ensemble Incontemporain (from their FB page)

INORI belongs to Stockhausen’s engagement with Japanese music. This does not fit into the bifurcation of 1. dodecaphony as culmination of absolute music with its attending Germanic baggage; versus 2. non-Western avantgarde characteristics astools of the (countercultural?) opposition. It was a meeting of ceremonial Japanese aesthetics and serial systemization that drove Stockhausen’s integration of music and gesture in INORI. This becomes a major feature of his compositions – particularly when the musicians themselves perform the choreography (see Harlekin and much of LICHT). These works enter conversation with the Cage/Cunningham collaborations and certainly Meredith Monk as postmodern interventions to dance.

Regarding the music: it’s almost better to not know the macrostructure and just let it wash over you. Sure, begin with pulses (PART I: RHYTHM); intensify or mollify by adding and subtracting energy (II: DYNAMIC); quicken pulses to change frequency on the axis of time (III: MELODY); modulate multiple frequencies simultaneously to create vertical alignments (IV: HARMONY); develop the diagonals of the previous two categories (V: POLYPHONY). These occur in a most satisfying way; but it is not quite so a linear process of adding parameters. It’s the gradual, teasing exposition of the INORI melody; unlike Mantra, we have to wait for it.

The opening morse code pattern is easy to mark but also herky jerky, awkward: hardly an ear-catching minimalist groove. Yet it is highly repetitious, and Stockhausen’s orchestrally synthesized 60 timbre-dynamic levels are subtle modifications. The initially static twenty-five to thirty-five minutes relate most closely to the minimal techniques in Scelsci (see Quattro Pezzi su una nota sola). It’s as percussion and brass fill out the texture that things begin to move. There’s unusual-for-Stockhausen stuff ranging from Ives chorale to verklärte bowing (the beginning of the POLYPHONY); the tuba bubbling below tremolo strings and flute in the “Spiral” passage (V) leaves a deep imprint and sets up a grand ending.

ca. 1970 KS at the controls – from a Salon dot com article (2001)9

USEFUL LINKS

Stockhausen: Sounds in Space. The most amazing internet resource for a post-1950 composer. We are endlessly grateful to Ed Chang for his efforts.

Stockhausen Verlag Source for the (amazing) official scores and CDs, in addition to, books, DVDs, and other collectible items. Thanks to Kathinka Pasveer for her correspondence and help.

Stockhausen Performances from the Stockhausen Stiftung, this is a useful page to keep track of upcoming concerts.

Sonoloco: Stockhausen Verlag Reviews These are far more than reviews; Ingvar Loco Nordin’s writing on the composer is filled with important insights and first hand accounts. Another invaluable resource!

- I share this opinion and do struggle with some of the ’60s works. The short-wave pieces – fascinating notationally and to realize – and intuitive music especially leave me missing my favorite Stockhauseney stuff. With that said: Stimmung, Mikrophonie I / II, and Zyklus are the most compelling open form works I’ve encountered, and fully justify his efforts to cede composer control. ↩︎

- Stockhausen’s withdrawal of his music from Deutche Grammophon is probably another reason. The Stockhausen Verlag is an tremendous resource whose exhaustive releases make the best possible case for the composer’s legacy. Nevertheless, DG’s earlier vinyl releases appear to have made his work more widely available: they were (and sometimes still are!) at a more reasonable price point. It would be nice to reconcile these tendencies; perhaps that’s what youtube videos have done. ↩︎

- Lusche performs an excerpt here (please post the entire work!) ; Matthew Brown plays the entire piece over three videos, but only in recital-level recording quality. ↩︎

- The 19 moments of the open form No. 11 also have differentiated features and moods; but these only emerged for me through close study and comparison of realizations. ↩︎

- Reception for Vanessa Benelli Mosell’s 2016 album contain Klavierstück 12 was surprisingly positive. Eve’s kisses and other vocalizations are delivered with gusto by Mosell; she finds a humor that still works when divorced from LICHT’s characterizations ↩︎

- It reminds me of how RichardTaruskin describes the classical-era reformation of tonality: how Johann Christian Bach rhetorically dramatized the most commonplace tonal modulation to V and thereby established the dialectical potential of the secondary theme area in sonata. ↩︎

- See Levaux and Rose Vekony trans., We Have Always Been Minimalist: The Construction and Triumph of a Musical Style (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2020). ↩︎