Usually applied to people, music, and dress, punk’s slippery configuration of elements—sounds, attitudes, politics, feelings, materiality, sociality—can be variously assembled. One rarely needs all or most of these; hence the premise that punk is not a consistent musical style, even when common sonic and performance practices do tend to clump together. If punk music is more than the sum of its parts, then what are we to make of it as film? It may not be a movie genre, yet the utility of the term to bundle qualities together seems to persuade that cinematic punk does exist—and more substantively than through punk characters and settings. This is the first entry in a series of essays about what it means for a movie to be punk.

Macon Blair in Blue Ruin [1]

Green Room was Jeremy Saulnier’s hardcore-tinged follow-up to the intense Blue Ruin. The earlier picture’s narrative & filmmaking concision struck me then and now as punklike in their incisiveness—not to say the motion is fast: it’s moderate like “Black Coffee.” The writer-director’s aim to let punk inform the next film was reason for excitement. Saulnier fronted Virginia hardcore band No Turn On Fred in 1990s D.C. and recounted his experiences with scene violence & Neo-Nazis in press for Green Room:

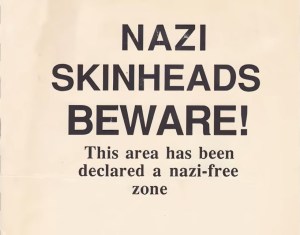

When I was in the hardcore scene, in the 90s, you had this insane expansion of subgenres: posi-core and emo-core and Krishnacore, and traditional hardcore and Baltimore style—that was big for me, tough-guy stuff. And when I went into DC in the 90s, there were lots of shows where Nazi skinheads were present. I was disheartened that some of my favorite-sounding bands, with incomprehensible death metal growl lyrics, when I’d read the liner notes or hear them in concert, I would see true hate, a very twisted ideology.[2]

Here, touring hardcore band the Ain’t Rights find themselves in the Pacific Northwest playing in a white supremacist den—where they must fight for their lives after witnessing a crime. One of the locals Amber becomes their ally in her own attempt to escape and avenge a friend. Green Room and Blue Ruin are rural thrillers with generic affinities to B movies and exploitation—according well with punk’s pursuit of affect in historically emergent rock styles. Green Room’s budget, star power, technical features, and mise en scene far exceed its predecessor’s humble means.These resources helped to build an uncannily 1990s/2010s setting[3] and to train the actors to be effective punk players.[4] Then why do I feel that this enjoyable, well-made thriller lacks the spark? It isn’t just the more ornate filmmaking. The casual enrollment of punk archetypes into Green Room leaves it lacking provocation.

GET IN THE VAN

Our protagonists quickly meet their local contact: zinemaker & gig fixer Tad—a true believer composed of artifacts like ‘77 punk garb, Fear: The Record (Tiger: “This dude’s legit”), and fliers for Conflict & Minor Threat; Bone Gatherer (?) and Warbringer (2004—) are more recent referents. The film assembles additional punk symbols out of time: an ancient “weathered conversion van” closer to Descendents iconography than contemporary vessel; a BMX bike; punk T-Shirts.

Tad, Tiger, Sam, Pat, & Reece at Tad’s pad in Green Room [5]

The Ain’t Rights are a 2010s hardcore-adjacent act after Saulnier’s ’90s Alexandria, VA band—more temporal drift. Conflicted bassist Pat is the director’s punk-theorizing mouthpiece, corporealizing 2014 thought in a past-inflected, Minor Threat-T-clad self. He forms the band’s brain trust with the DKs-clad Sam (guitar). Drummer Reece (“20s, a natural athlete”) evokes the 80s-90s suburban metalhead [6] and has little patience for punk ideals. Blue-haired singer Tiger is another true believer who justifies choices emotively (“This is not hard rock”!) that Pat makes through aesthetics:

Pat: Just—you gotta be there. The music is for effect. It’s time and aggression and…

Reece: Technical wizardry

P: …t’s shared live. And then it goes away. The energy, it can’t last,

Sam: Unless you’re Iggy Pop.

P: And good for him. I just don’t think I’ll be in my 70’s still listening to Minor Threat.

R: Tiger will. Right?

Tiger: I won’t live to be seventy.[7]

With Pat as Saulnier’s conscience, Reece the tattooed jock who values metal’s “technical wizardy,” Sam the savvy business-woman, Tiger as the live fast/die young, and Tad the lifelong scenester, characterization is reduced to archetypal punks. That is not a weakness and could be fruitful for dramatizing the issues around music scenes. Spike Lee is a master of this approach in a film like Do The Right Thing where writing characters as representational ‘types’ is efficient shorthand to create dense, socially revelatory scenarios. This does not hinder not hinder an ensemble cast from delivering excellent performances. But it disappoints how the Green Room character archetypes do not enter into Lee-style dialectics of class, race, and gender…despite the presence of freakin’ Neo-Nazis.

“IN A REAL FOURTH REICH YOU’LL BE THE FIRST TO GO”

Saulnier stages his thriller centerpiece in a white-supremacist stronghold where Tad arranged a last-minute gig. The infiltration of 1980s and ’90s scenes by Neo-Nazis and affiliated racists is well-attested by many including the director. In a 2006 study of white power scenes, sociologists Robert Futrell et al.found that privacy had become essential: white supremacists organized musical events where they could ensure security and vet attendees in advance.[8] If it is unlikely that a white power sanctuary would welcome the Ain’t Rights, it remains an effective setup for the hate group to control the space and the punks to be the infiltrators.

The Ain’t Rights play for Neo-Nazis

Pat, like Anton Yelchin himself, is a Jewish character—Sam inappropriately threatens to reveal this to *actual Nazis* if he won’t accede to open with Dead Kennedys. She is played by Alia Shawkat who is of Iraqi descent. Neither textual nor subtextual possibility is activated, and potential destabilization via the DK’s “Nazi Punks Fuck Off” does not pay off: the ensuing (mild) reaction would not make Biafra blink. Punk’s disruptive capacity is strangely limited throughout. The white supremacists are not threatened–they just want loudness to power their collective anger, regardless of ideology. The Ain’t Rights aren’t ethically troubled or fearful to perform: aside from the note to play “earlier stuff,” it’s a gig. They don’t believe in music or themselves as political agents.

Sam: How much?

Tad: $350, minus your tab. And just so you know: it’s mostly boots and braces down there.

Tiger: Skins? There’s some at every show.

Playing the DKs number is more gag than protest. When the Ain’t Rights become targets, it is because they witnessed a crime—their identities and beliefs are of no consequence.

Violence enters the narrative and Green Room pivots into a stylized indie action flick. That may be uncharitable, but what else are we to make of warpaint-emblazoned Pat & Amber or the latter’s shotgun-wielding gusto? Read according to a conventional story arc, the fight for their lives is the site of narrative Bildung or self-discovery. Amber’s backstory emerges through racism apologia:

Pat: So I’m curious. You’re smart…I don’t see how you fall for this shit…

Amber: I didn’t fall for anything. I was raped once and mugged twice. Let’s just say none of them were white.

Pat nods, gulping water.

P: Any of them women?

A: It’s a problem where I grew up.

P: What about tonight? Think we gotta white people problem?

A: Fuck you.

Her empowerment implies that she is ready to move on from past trauma. So should we predict that she will also reject white supremacy—optimistic when her only evident development is to discover a hidden brutality? A character-arc rationale for dragging the movie into the revenge world of a neon-bathed Mandy (2018) is unsatisfying. Blue Ruin is also a revenge and survival film but it centers loss: deaths are harrowing and without triumph, as the protagonist is forced into an epiphany. Meanwhile, Amber and the Ain’t Rights emerge from their green chrysalis as action heroes who deliver cool kills and cool lines.

Pat and Amber

That may be too cheeky. I do believe Jeremy Saulnier intends more for the band. He sketches an additional shared arc inspired by the punk musician’s journey. There are indications throughout that the Ain’t Rights have outlived their musical relationship and outgrown the scenes & zines. Underground punk means is a meager living outside of the cultural capital to know people and to have good taste. That is alright for Tiger; Sam and Reece seem ready for musical endeavors that pay in money; Pat probably doesn’t need to play music at all. Punk is just a season for most, it seems.

When the Ain’t Rights select an all-time ‘desert-island band,’ their initial instinct is to articulate good taste: Poison Idea (Sam), the Damned or Misfits (Tiger), and the Cro-Mags or Black Sabbath (Reece) have a legitimacy also represented by the DKs and Minor Threat tees. But Pat won’t be in my 70’s still listening to Minor Threat because for him, punk’s orientation in lived musical practice and youth spaces has a built-in time limit. The director’s Bluray commentary is in close sympathy with Pat’s effect… time and aggression / shared live…then it goes away / energy, it can’t last conception.

Senior Threat (via Brian Baker’s insta)

Punk impermanence: it only reaches fruition through fleeting articulation in a specific moment & place—the opposite of timeless.

When our heroes are at death’s hand, they have nothing to conceal: Reece’s championed desert-island music is actually Prince; Sam’s is Simon & Garfunkel; Tiger’s remains the Misfits; Pat never says, although Saulnier later acknowleged Creedence Clearwater Revival.[9] I’m not sure how to accept that these kids are killing themselves for punk when it is at best value-neutral aesthetics of amplified affect(Pat, Saulnier) or an unlikely means of success (Sam, Reece). Tiger’s deeply felt dedication hinges meanwhile on misguided identification with Darby Crash. Why not identify with Aus-Rotten, Bikini Kill, Crudos, and Fugazi[10]? It’s strange to choose this life yet believe so little in punk’s ethical potential & sound’s political efficacy…of course, then they wouldn’t be playing for Nazis.

Green Ruin (2015)

Directed & written by Jeremy Saulnier

Shot by Shawn Porter Edited by Julia Bloch Music by Brooke Blair & Will Blair

Starring Macon Blair, Joe Cole, Imogen Poots, Alia Shawkat, Patrick Stewart, Callum Turner, Anton Yelchin

[1] Blue Ruin screen grab from https://film-grab.com/2014/12/03/blue-ruin/

[2] https://www.bkmag.com/2016/04/12/jeremy-saulnier-green-room/

[3] Cinematographer Shawn Porter: We had to piece together our own story about the venue’s history. Maybe when Patrick Stewart’s character bought the place he added a new light over the bar and maybe a couple black lights, but other than that it’s been left untouched. Even leaving a few old remnants of what came before, like maybe it was a VFW hall. I think creating this visual history of the club aided in creating its unique ugliness.

[4] Hutch Harris helped coalesce the band. See https://www.talkhouse.com/aint-rights-right-four-days-green-room/

Lisa Schonberg, http://www.lisaschonberg.com/ worked with Joe Cole on the drums

[5] Green Room screen grabs from https://film-grab.com/2016/10/21/green-room/

[6] Saulnier: When I was there, there was so much infusion of metal. Krishnacore. Vegan kids. A trend was wearing letterman jackets like jocks. Tattoos, too. See https://www.avclub.com/green-room-director-jeremy-saulnier-on-going-punk-and-g-1798246274

[7] Excerpts from the screenplay are from Jeremy Saulnier Green Room Screenplay, Script Status September 7, 2014. See https://www.scriptslug.com/script/green-room-2015

[8] See Robert Futrell, Pete Simi, and Simon Gottschalk. “Understanding Music in Movements: The White Power Music Scene,” The Sociological Quarterly 47/2 (2006): 275–304.

[9] See https://www.reddit.com/r/movies/comments/9l1y1e/i_am_jeremy_saulnier_hold_the_dark_blue_ruin/e73ejip/?context=8&depth=9 D. Boon might say the same; but of course these characters were born in the 1990s!

[10] The Ain’t Rights actually have a Fugazi sticker on their van. I am uncertain if this is unintentional irony; of course Fugazi didn’t even sell stickers!